Shawn Crahan struggles for a moment to imagine what the Clown of 1999 might say were he to find himself in conversation with the Clown of 2024. Much has changed over the last quarter-century, both within the realm of Slipknot and beyond it. Attitudes towards alternative and extreme music, and their compatibility with the ‘mainstream’, have shifted immeasurably, thanks in no small part to the band with which he and his fellow masked misfits rose to prominence. Tragedy and tribulation have seen membership of The Nine changed almost by half. But perhaps most pertinently, age, injury and the kind of arenas in which they now ply their trade have switched up the rules of engagement under which they wage war against the world.

“That younger Clown would probably tell me to get up off my ass,” Shawn smiles, wryly. “But that Clown has beaten himself into submission over the last 25 years, in pursuit of this vision. My brain still wants to go 24-hours-a-day, and I’d still love to be out there doing flips into the crowd, but my body hurts, so I’m limited nowadays. Like how I’m having problems with my left knee right now. It just dislocates on its own and I have no idea why. Back then, I wouldn’t care. So many people want to see that old Clown again. But he’s a hard Clown to talk to, a harder Clown to impress, an even harder Clown to find nowadays. That old Clown smirks a lot at the current Clown. And rightly so. If this ‘new’ Clown had to be that old Clown again, I don’t think there would be any Clown at all…”

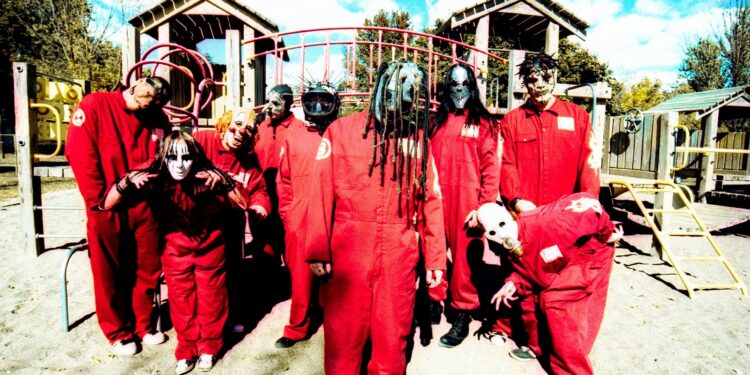

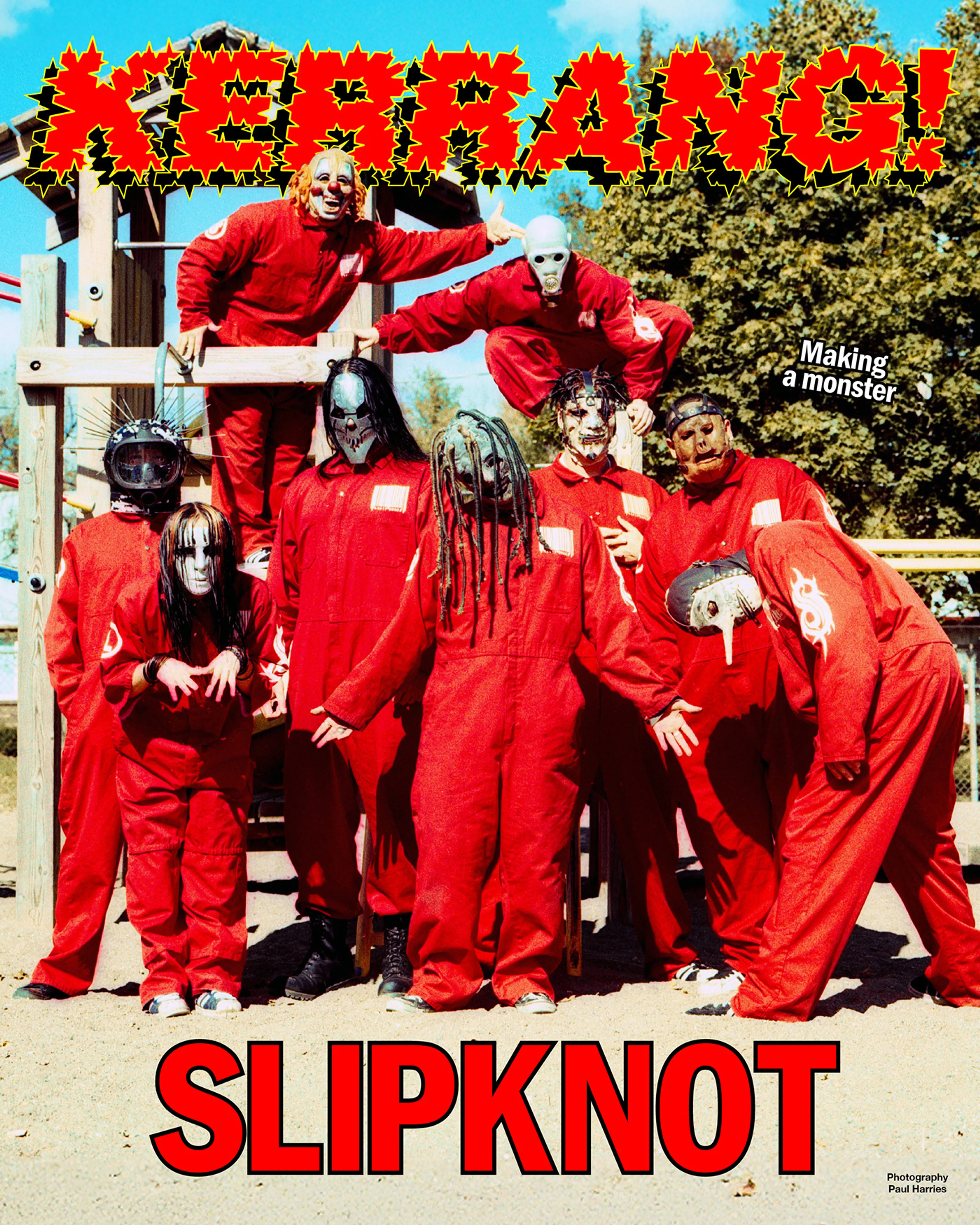

Stripped-down, sold-out and unapologetic in their savagery, the first dates of the final leg of Slipknot’s 2024 Here Comes The Pain tour at Leeds’ 14,000-cap First Direct Arena and Glasgow’s similarly-sized OVO Hydro don’t feel compromised. Wear and tear are inevitabilities, but compared to the pit veterans old enough to remember the last time the ’Knot delivered a set entirely of pre-millennial material, the figures onstage look positively sprightly. Costume plays its part, masking the maturation of a line-up now mainly in their late-40s and 50s. Reconnection to the old electricity is crucial, too: the feral immediacy of a performance built around songs like (sic), Surfacing and Scissors contrasting sharply with the bells, whistles and radio hits of the statelier sets to which we’ve grown accustomed. Rather than just pulling on the old red boilersuits and stepping back in time, however, Clown insists that it’s about never relinquishing the defiance inside.

“Twenty-five years ago, getting into those red coveralls, I didn’t feel goofy,” he picks up with a frown. “But I feel goofy in them now. Seriously, how do you [revisit] something that changed your whole life? The world was different. The fans were different. Rock’n’roll was different. Even Kerrang! was different back then. At the same time, I think the old Clown would be proud to see how hard the new Clown works to still be the Clown, and how I don’t do what I do for anyone but myself. Clown doesn’t partake for money or fame, ego or popularity. It’s still about the inner turmoil; about trying to forgive yourself through performance; about getting out there day after day, year after year, to rejoice with people that you love and music that you’d die for; about cutting yourself open and letting all the filth and disgust bleed out. And there’s been a lot of blood lost. A lot of blood…”